How Paranoid Is Your Android?

Published:

This post was written as an assignment for ASEN 6519, the Advanced Survey of Sequential Decision Making class, at CU Boulder. AI was used to help with research for this post and perform a grammar/tone check.

A Motivating Example From Class: Robot Soccer

It’s no longer a surprise when we learn that AI agents can accomplish superhuman intellectual feats. The emergence of powerful chatbots with deep implicit knowledge bases and impressive abstract reasoning capabilities has helped rocket NVIDIA to a market cap of over $4 trillion. It’s fairly widely accepted that the models underlying these agents are basically next-token prediction machines. The key to their success is that the next-token prediction task has nearly unlimited training data available, in a form which exactly matches the task at hand (since all you need is just human-generated text).

In many tasks of real-world interest though, this training data doesn’t exist, and self-supervision isn’t sufficient. Maybe you have some camera data from driver behavior on the road, but it won’t exactly match the camera position of your self-driving car. Maybe you can simulate your robot, but there will be some real-world dynamics which your simulator has failed to model.

It’s especially this second problem, called sim-to-real transfer, which I want to focus in on. In one recent triumph (Haarnoja et al. 2024)1, a Google DeepMind team trained robots to play soccer in a simulator, and then transferred the simulated policies directly to real robotic hardware, without additional training:

We just released our work on robot soccer. I've been working on this for quite some time with my amazing colleagues at DeepMind. It's exciting how deep RL can produce such beautiful behaviors with low-cost robots. Full paper is available at https://t.co/A65rPLL7UD Enjoy! pic.twitter.com/n8j4uELhIL

— Tuomas Haarnoja (@haarnoja) April 27, 2023

You may notice that these robots, while both cute and impressive in their way, seem to fall almost constantly.

In my opinion, the robot soccer project points to multiple key issues in robotic learning:

- The need to transfer skills from a simulator to real hardware. Even the Haarnoja paper, which declares victory in zero-shot sim-to-real transfer, shows a measurable (although not extreme) drop in performance from sim to real.

- Even when you have successful sim-to-real transfer, you can end up with learned behaviors which are qualitatively fragile. In a real application, a robot which is constantly falling is likely to need a prohibitive amount of maintenance. And in fact, the paper acknowledges in a small aside that the robot performance “degraded quickly over time,” requiring the authors to “regularly perform robot maintenance routines.”

So I wonder whether the sim-to-real problem was fundamentally solved in the robot soccer paper. Perhaps the field needs to combine the paper’s bag of randomization tricks during simulation with a more principled and thorough approach to avoiding failures in the field. This post aims to discuss theoretical frameworks and approaches to dealing with these important issues.

Enter Robustness

Addressing problems of fragility and environment shifts falls under the broad category of “robust reinforcement learning (RL).” To go up one level of abstraction, robustness may aim to address fragility arising from:

- Model misspecification. Developers of AI systems often don’t correctly model the world. Maybe they base their robot on an explicit physics model that makes simplifying assumptions. Even in highly flexible learnable models, developers assume that experiences from the world (transitions and rewards) are i.i.d., and that the distribution from which these experiences are drawn is stationary over time. In sim-to-real transfer, it is this second assumption that is almost always violated, since there is a distribution shift when the system is deployed in the real world.

- Epistemic uncertainty. Even when we’ve correctly chosen the class of model for the world (or at least, correctly enough), when we’re trying to do reinforcement learning, we need to estimate the parameters of that model. Since we are basing our estimates on data, our estimates will have some error. A system which is robust to epistemic uncertainty will exhibit a kind of pessimism under this uncertainty. Notice though, we’ve changed the game a little – whereas typically in RL, we’re aiming to maximize expected discounted reward, when we factor in robustness, it’s because we’re asymmetrically averse to “unpleasant surprises”. This is what’s typically called “Safe RL.” Approaches to mitigate model misspecification often can also be applied to mitigate epistemic uncertainty and make RL safer.

- Aleatoric uncertainty. Once we’re in the land of “Safe RL,” and we’ve decided that we’re asymmetrically risk-averse, there’s no reason to stop at epistemic uncertainty. Robustness can also encompass a preference for avoiding known risks by taking actions which have only a narrow range of possible outcomes, all of which are acceptable.

So, robustness can refer to strategies for managing almost every kind of uncertainty we have in automated decision-making. The unifying characteristic of robustness is a focus on limiting the damage from worst-case, or nearly worst-case, scenarios. In short: paranoia!

Robust Planning

The cornerstone of sequential decision-making, including RL, is planning ahead. Robust planning means planning for worst-case contingencies. We can formalize this with the robust MDP.

Robust MDPs

If RL begins with the Markov Decision Process (MDP), robust RL begins with the… RMDP, or robust MDP. (See Suilen et al.2 for an overview of RMDPs – much of the content of this section summarizes that article). Robust MDPs focus on managing model misspecification, although in the learning context, they can also be useful for managing epistemic uncertainty, if we view the estimation error as a kind of model misspecification.

We recall that an MDP is defined by a tuple \((S, A, T, R, \gamma)\), where \(S\) is the set of states, \(A\) is the set of actions, \(T: S \times A \to \Delta(S)\) encodes stochastic transitions and \(R: S \times A \to \mathbb{R}\) encodes deterministic rewards. Note that \(R\) is frequently bounded on one or both sides.

A robust MDP is defined similarly by a tuple \((S, A, \mathcal{T}, R, \gamma)\). The difference is that instead of a single transition function \(T\), you have a map \(\mathcal{T}: \mathcal{U} \to (S \times A \to \Delta(S))\) to represent our uncertainty about what the transitions might be.

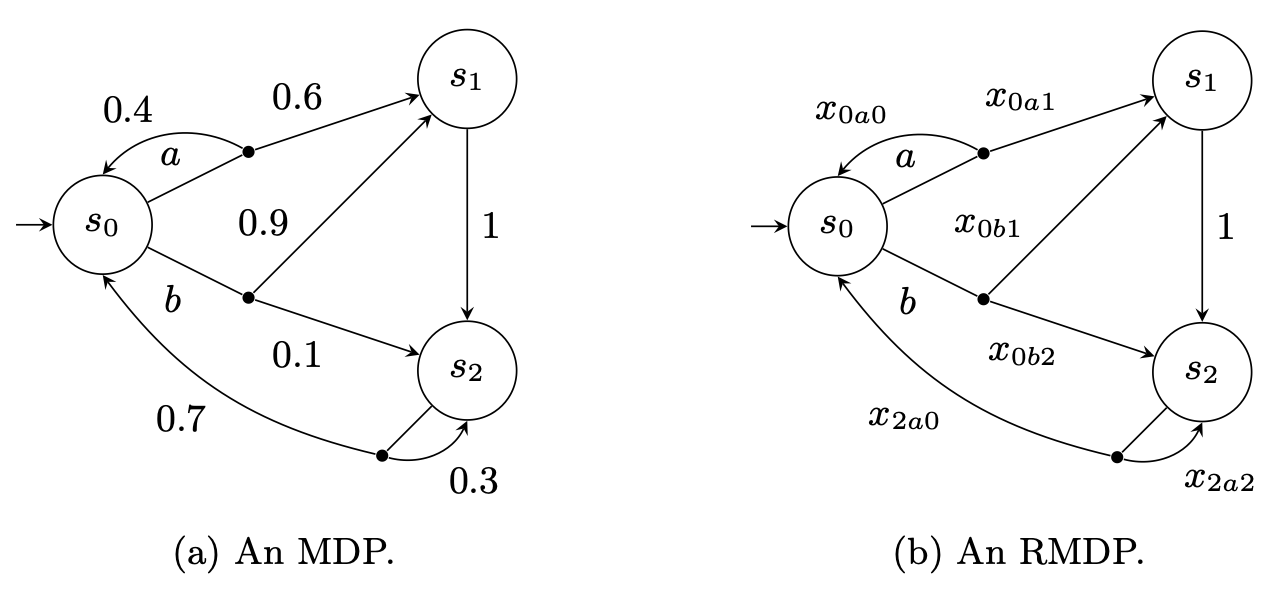

\(\mathcal{U} \subseteq \mathbb{R}^X\) for some set of variables \(X\), is called our uncertainty set. We can think of the uncertainty set as representing our set of possible variable assignments to the actual transitions. Typically, we’d take \(X = \{x_{sas'} \mid (s, a, s') \in S \times A \times S \}\). So, for a given assignment \(f\) from \(\mathcal{U}\), and a given transition \(s, a, s'\), we get a transition probability \(T(s, a, s') = f(x_{sas'})\). This diagram might help with understanding:

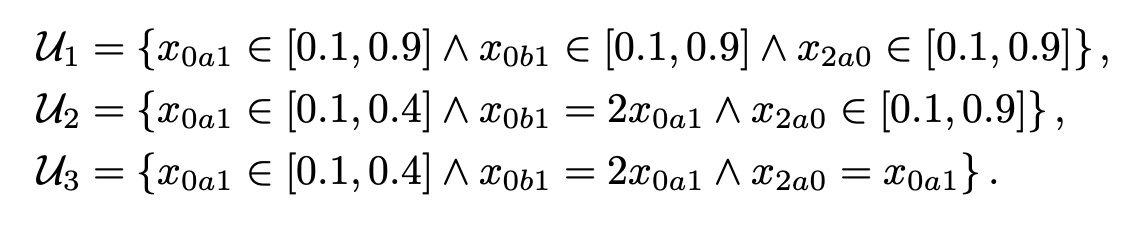

We can define uncertainty sets to indicate that the variable transition probabilities must obey certain constraints:

(Both images from Suilen et al.)

In a robust MDP, the planner must maximize expected reward under the worst-case realization allowable by \(\mathcal{U}\).

A Technical Detour

We notice that uncertainty sets can encode all kinds of dependencies between the unknown transition probabilities. These dependencies can make analyzing RMDPs difficult. So, we often make a simplifying assumption of rectangularity, or independence. We can consider either independence between states (\(s\)-rectangularity) or the stronger condition of independence between states and actions, called \((s, a)\)-rectangularity. In the example screenshotted above, \(\mathcal{U}_1\) is \((s, a)\)-rectangular, but \(\mathcal{U}_2\) is only \(s\)-rectangular. These conditions have implications for the difficulty of policy evaluation. For convex \(\mathcal{U}\), rectangularity allows us to evaluate policies in polynomial time.

Solving MDPs and RMDPs

If we have an MDP, the standard value iteration approach to reward maximization involves computing the value \(V(s)\) of each state – that is, the reward you can expect to get from that state if you behave optimally. We identify the value via an iterative computation called the Bellman operator, which provably converges:

\[V^{(n+1)}(s) = \max_{a \in A}\left\{ R(s,a) + \gamma\sum_{s' \in S}T(s, a, s')V^{(n)}(s') \right\}\]In an RMDP, our goal again is typically to find a worst-case value across all possible transitions \(T \in \mathcal{T}\). In other words,

\[\underline{V}^{(n+1)}(s) = \max_{a \in A}\left\{ R(s,a) + \gamma \inf_{T \in \mathcal{T}} \left\{ \sum_{s' \in S}T(s, a, s')\underline{V}^{(n)}(s') \right\}\right\}\]With this seemingly small change to the Bellman operator, we’ve formalized the worst-case planning problem!

Why Rectangularity Helps

Notice that if we have an \((s, a)\)-rectangular uncertainty set, we don’t need to optimize over the entire uncertainty set – only the possible values for the current transition:

\[\underline{V}^{(n+1)}(s) = \max_{a \in A}\left\{ R(s,a) + \gamma \inf_{T(s,a) \in \mathcal{T}(s, a)} \left\{ \sum_{s' \in S}T(s, a, s')\underline{V}^{(n)}(s') \right\}\right\}\]which is a much easier optimization problem.

Connections to Games

Suilen et al. points out that the RMDP formalism can be expressed as a two-player, zero-sum stochastic game (SG) between the agent and an adversarial Nature which tries at every turn to minimize the agent’s reward. The agent’s moves consist of actions in an RMDP, and Nature’s moves consist of selections from the uncertainty set.

Because this setting is a “2P0S” game, it doesn’t require advanced game theoretic machinery to solve. But I find the game-theoretic view here interesting anyway, since it draws out connections between robustness and multi-agent RL. And, it might point the way towards relaxations of the conservative robust worst-case view, since it seems highly implausible that Nature is generally playing a zero-sum game with us… More on this at the end.

Learning Robustly

Ok! So we have a formalism for worst-case thinking. But this post didn’t just promise to talk about robust planning – it started by talking about learning! When it comes to robust learning, there are a lot of very different approaches. I’ll try to touch on the major ones. Some are based on the RMDP formalism, while some of them are more just practical techniques for robust learning. As my main reference, I’m using a recent survey of robust RL.3

Learning Robust MDPs Directly by Learning Uncertainty Sets

One theoretically-grounded approach to robust learning involves adaptive uncertainty sets which become narrower as more data is collected. This comes back to the idea of viewing epistemic uncertainty as a kind of model misspecification. Robust value functions and robust policies, which are pessimistic under epistemic uncertainty, can provide high-probability guarantees of performance.

Uncertainty estimation can use confidence intervals from concentration bounds like Hoeffding’s to build uncertainty sets. Whereas learning in classic MDPs might look at confidence intervals to provide PAC or regret guarantees, in the robust setting, confidence intervals can actually define what we consider to be “worst case.”

Beyond the frequentist confidence interval, there seems to be a wide variety of approaches to learning uncertainty sets:

- Some research takes a Bayesian approach to learning RMDPs. In particular Derman et al. 20204 propose a Bayesian DQN algorithm (along with some theoretical analysis) which promises both robustness and adaptiveness to non-stationary dynamics. This adaptiveness is especially interesting, since it helps potentially alleviate the “overly conservative” tendencies of robust RL.

- “Distributionally robust RL” takes a slightly different tack. Rather than identifying uncertainty sets as confidence intervals, distributional approaches build an uncertainty set based on a “ball” of probability distributions, e.g. by using KL divergence regions around the optimal policy from each state.5 Beware: it seems that there is a lot of fuzziness in the literature around “robust RL”, “distributionally robust RL”, “distributional RL”… and that the boundaries between these approaches are not super well defined.

Risk-Sensitive RL

Similar to robust learning (but not taking a hard worst-case view of the problem) is risk-sensitive RL, which uses explicitly risk-averse transformations of the reward, for example, CVaR6, to train risk-averse policies and avoid catastrophic outcomes.

Conservative Q-Learning

One successful approach, called conservative Q-learning7, regularizes Q function approximation to underestimate Q values out-of-distribution, effectively biasing assumptions towards the worst-case and “robustifying” the resulting policy.

Adversarial Training

Perhaps motivated by the conception of robustness as a game between the agent and nature, many approaches to robust RL attempt to expose the agent to a wide variety of conceivable scenarios during training. Sometimes these will just be randomization or noise in the simulator (as the robot soccer developers did, or the paper we saw earlier about trajectory design8). Many approaches, however, take it to another level, and attempt to task an adaptive adversary (often another neural network) with tweaking simulator parameters to thwart the performance of the agent.9

A Relatively Open Area: Exploration

Some recent work10 suggests that exploration has not really been considered in robust RL. I’m not sure that’s entirely fair – I did notice that Smirnova et al. discussed how entropy regularization could encourage exploration under their KL-based scheme. However, I do wonder whether there may yet be a lot of ideas to explore around exploration with robustness.

One simple idea I was able to generate in this area (so no guarantee that it’s any good!), is to model your uncertainty sets as literally the entire range of the data you’ve seen so far from a given state-action pair (maybe with some interpolation in the continuous case). From there, if you plan for worst-case results under those uncertainty sets, you will naturally explore, since lesser-explored states are less likely to have experienced an unusually bad event.

Between Robustness and Optimality

I’ll finish this post with a mention of one very cool area in the realm of robust RL/robust control, which aims to help address the over-conservatism of many robust approaches. It’s called “non-stochastic control.” It was initially developed in a flurry of activity within a small community around 2020, but has perhaps died down a bit. One of the original instigators of this idea, Elad Hazan, seems to still be working on a book about it11.

In essence, Hazan proposes taking an approach which uses ideas from adversarial online learning to minimize regret instead of maximize rewards. This approach, in my understanding, embraces the idea that Nature is playing a game, but does not assume that this game is known beforehand or is zero-sum. Instead, it attempts to learn Nature’s game and play optimally against it, whether Nature is thwarting the agent, or helping it.

Hazan’s book mentions RL but seems mostly focused on classical control. Extending some of his ideas to the full RL setting sounds very interesting. Perhaps it could help us make our androids a little less paranoid, while still remaning… safely deployed.

Haarnoja, T., Moran, B., Lever, G., Huang, S. H., Tirumala, D., Humplik, J., … & Heess, N. (2024). Learning agile soccer skills for a bipedal robot with deep reinforcement learning. Science Robotics, 9(89), eadi8022. ↩

Suilen, M., Badings, T., Bovy, E. M., Parker, D., & Jansen, N. (2024). Robust markov decision processes: A place where AI and formal methods meet. In Principles of Verification: Cycling the Probabilistic Landscape: Essays Dedicated to Joost-Pieter Katoen on the Occasion of His 60th Birthday, Part III (pp. 126-154). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. ↩

Moos, J., Hansel, K., Abdulsamad, H., Stark, S., Clever, D., & Peters, J. (2022). Robust reinforcement learning: A review of foundations and recent advances. Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction, 4(1), 276-315. ↩

Derman, E., Mankowitz, D., Mann, T., & Mannor, S. (2020, August). A bayesian approach to robust reinforcement learning. In Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence (pp. 648-658). PMLR. ↩

Smirnova, E., Dohmatob, E., & Mary, J. (2019). Distributionally robust reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1902.08708. ↩

Hiraoka, T., Imagawa, T., Mori, T., Onishi, T., & Tsuruoka, Y. (2019). Learning robust options by conditional value at risk optimization. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 32. ↩

Kumar, A., Zhou, A., Tucker, G., & Levine, S. (2020). Conservative q-learning for offline reinforcement learning. Advances in neural information processing systems, 33, 1179-1191. ↩

Zavoli, A., & Federici, L. (2021). Reinforcement learning for robust trajectory design of interplanetary missions. Journal of Guidance, Control, and Dynamics, 44(8), 1440-1453. ↩

Schott, L., Delas, J., Hajri, H., Gherbi, E., Yaich, R., Boulahia-Cuppens, N., … & Lamprier, S. (2024). Robust deep reinforcement learning through adversarial attacks and training: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.00420. ↩

Lu, M., Zhong, H., Zhang, T., & Blanchet, J. (2024). Distributionally robust reinforcement learning with interactive data collection: Fundamental hardness and near-optimal algorithms. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 37, 12528-12580. ↩

Hazan, E., & Singh, K. (2022). Introduction to online nonstochastic control. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.09619. ↩